In TradFi, buying Apple stock looks simple: click “buy” and see the shares appear in your account. Under the hood, however, the pipeline is layered: a broker routes your trade, an exchange matches it, a custodian safeguards the asset, and a clearing house finalizes settlement. For retail investors, this complexity is abstracted away by brokers like Robinhood, Trade Republic; for institutions, by prime brokers such as Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan.

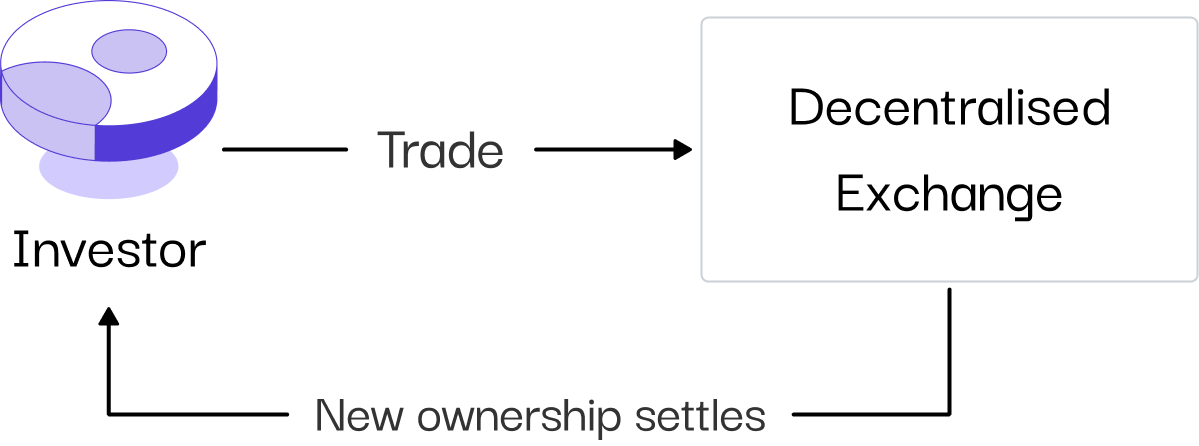

Decentralized Exchanges (DEXs) powering spot markets operate on blockchains and compress all of this into a single on-chain primitive. The DEX itself is a program that facilitates peer-to-peer trades without intermediaries, while inheriting self-custody, censorship resistance, and settlement guarantees from the underlying blockchain.

Today’s DEX landscape is diverse. Some protocols operate across multiple blockchains, such as Uniswap or Curve. Others are native to a single chain, like Aerodrome on Base. Alongside these venues, DEX aggregators such as 1inch, CowSwap or Velora sit one layer above, routing orders across multiple exchanges and liquidity sources to achieve the best available prices and execution.

From traditional to on-chain: a comparison of trade lifecycles

Traditional spot markets, where are we going from?

In traditional spot markets, brokers route orders to CLOB-based exchanges such as NASDAQ, where all buy and sell orders are collected into a single order book and matched based on price–time priority.

The trade lifecycle varies slightly depending on its origin.

Retail flow is often sold by brokers to market makers through a practice known as payment for order flow (PFOF). Instead of sending the order directly to a public exchange, the broker routes it to a market maker (e.g. Citadel), which executes the trade internally and pays the broker for that order flow. This can result in fast execution and potential price improvement for retail users, while the market maker profits from the spread.

Institutional flow is typically handled by prime brokers, which act as intermediaries managing execution and settlement on behalf of their clients. These prime brokers may:

- Route orders directly to exchanges

- Request quotes from liquidity providers via RFQs (Request for Quote systems)

- Execute trades in dark pools to reduce market impact and information leakage

In both cases, execution of a trade refers only to an agreement on price and size; the assets do not move yet. Settlement, the actual exchange of cash and securities, occurs later, typically one business day afterward. Clearing houses sit at the center of this process as the counterparty to every broker, market maker, and trading venue. They require margin to cover default risk and net positions so that only final exposures are settled. If a counterparty defaults, the clearing house can draw on posted margin to complete the trade.

Custodians, meanwhile, safeguard securities on behalf of brokers and investors, while the central securities depository (such as the DTC) updates electronic records to reflect changes in ownership. In practice, this means securities do not physically move; instead, ledgers at the depository and custodial levels ensure that property rights are accurately recorded.

In summary, with traditional spot markets:

- Capital efficiency is high because settlement is delayed. Market makers do not need to pre-fund every quote; instead, they post collateral with the clearing house and leverage their balance sheet across multiple markets and venues.

- At the same time, costs and risks are elevated because the stack relies on many intermediaries. Each additional layer introduces operational complexity, counterparty exposure, and potential single points of failure. If a clearing house halts, markets stall. If a major counterparty defaults, the settlement pipeline can seize up. And because the system is custodial by design, operational failures or fraud at service providers can translate directly into losses.

Reinventing spot markets through decentralization

A DEX is simply a program deployed on a blockchain that autonomously, trustlessly, and deterministically facilitates trades between user wallets.

Three execution paradigms exist: Automated Market Makers, Central Limit Order Books, and RFQ or intent-based systems. In practice, AMMs dominate on-chain spot markets, while RFQ systems are steadily gaining share.

The automated market maker revolution

Blockchains impose structural constraints: block latency, costs associated with every state transition, and throughput limits by design. The order book model requires market makers to continuously place and cancel orders at high frequency, a level of throughput that is not feasible on decentralized blockchains.

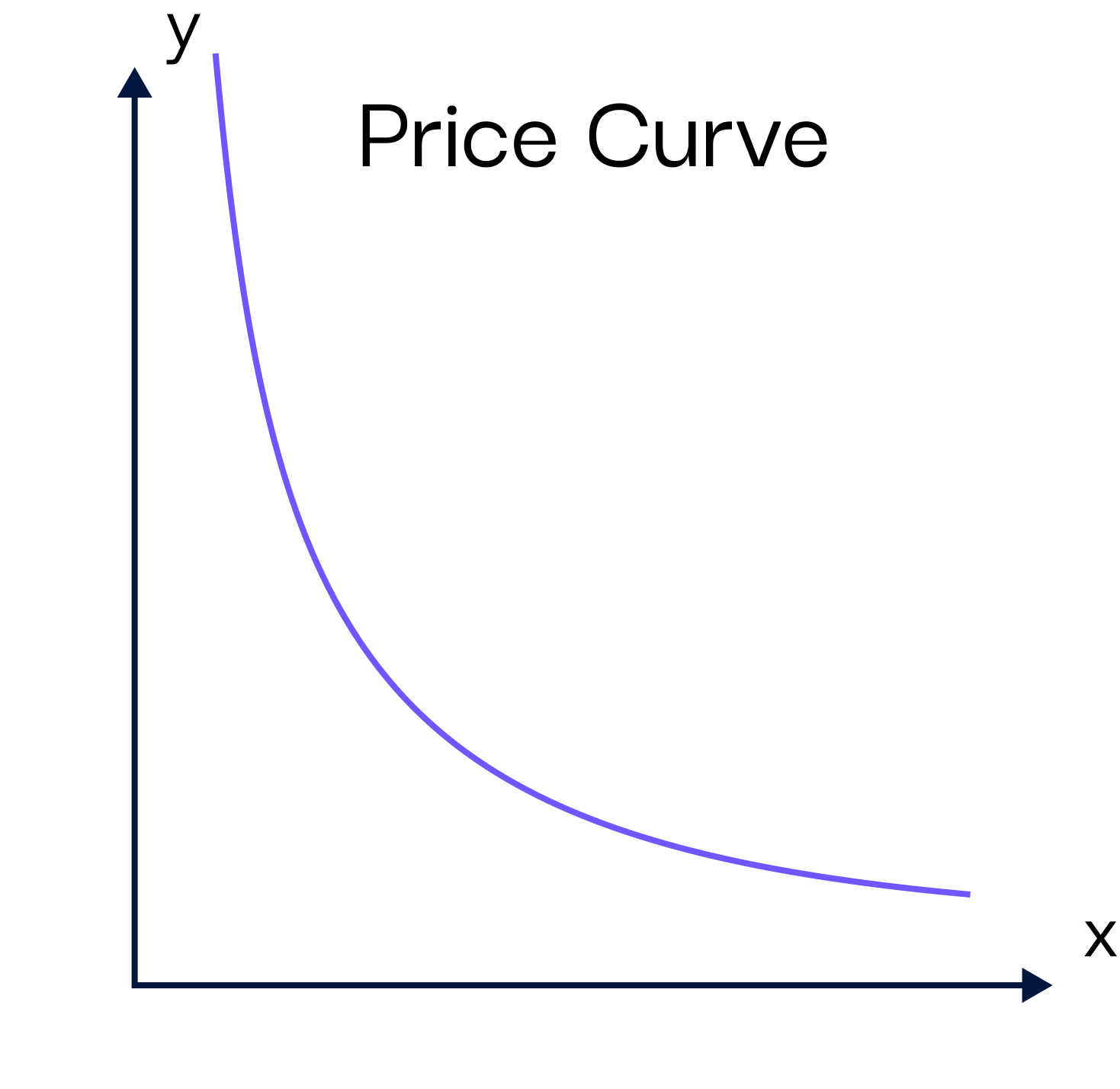

AMMs sidestep these constraints by pooling liquidity upfront and quoting a continuous price from a deterministic curve. Each trade moves the pool balances along that curve.

The most common design is the constant-product invariant pioneered by Uniswap, where k = quantity of asset X × quantity of asset Y. With concentrated liquidity, liquidity providers allocate capital within chosen price ranges (ticks), approximating an order book through many narrow bands of liquidity.

Conceptually, you can view an AMM as a subset of an order book: its pricing curve can be represented as a set of resting limit orders. The order book is the more general primitive; concentrated AMMs are a constrained, bandwidth-efficient design optimized for blockchains.

Advantages of Trading via DEXs

- Self-custody: No broker, no custodian, and no intermediary counterparty risk.

- Open and censorship-resistant: Anyone, anywhere can participate through permissionless access, broadening the reach of capital markets.

- Instant settlement: No clearing delays, no intermediary fees, and no trade counterparty risk.

- 24/7 operation: Markets run continuously without downtime.

Trade-offs

- Capital efficiency: Market makers must pre-fund liquidity. Without delayed settlement, assets sit idle until traded, reducing balance-sheet efficiency compared to traditional markets.

- Latency leakage: Block times make quotes stale, creating opportunities for arbitrageurs. Market makers bear this cost, often referred to as loss versus rebalancing (LVR).

- Pricing competitiveness: Because AMM liquidity is passive, pricing is generally less competitive than in fast, active CLOB-based markets.

Improving on-chain spot markets

The design space is evolving rapidly to address the two main challenges facing on-chain spot markets today: latency leakage and capital efficiency.

Faster block times.

Ethereum Layer-2s are reducing block latency. Tighter blocks fewer stale quotes, less arbitrage leakage, and higher throughput. In turn, this supports greater trading volumes and higher fee generation for market makers.

Off-chain RFQ systems.

RFQ systems such as 0x, or intent-based auction mechanisms like CowSwap, introduce a more active form of liquidity provision on-chain. Rather than relying on passive, resting liquidity that can be arbitraged, traders broadcast quote requests off-chain to professional market makers. These market makers respond with executable prices, sourcing liquidity across multiple venues, including AMMs, other market makers, or their own inventory.

By combining off-chain price discovery with on-chain settlement, RFQ systems bridge traditional market-making logic and decentralized infrastructure, bringing on-chain execution closer to the pricing efficiency of off-chain CLOBs.

Capital efficiency via composing financial primitives

Fluid DEX pioneers the integration of a money market directly with an exchange. Idle funds held in AMM pools accrue money-market yield by default, while debt positions can simultaneously be deployed as active liquidity within the pool. This composability improves capital efficiency by allowing the same assets to serve multiple financial functions at once.

Active market making via proprietary AMMs.

On Solana, so-called “prop AMMs” allow a single professional market maker to operate their own AMM using a custom pricing curve that can be updated extremely cheaply. Rather than cancelling and replacing orders as in a CLOB-based market, the market maker simply pushes parameter updates to the curve. Because these updates are inexpensive and can be applied before trades execute, such AMMs are largely insulated from toxic flow and loss-versus-rebalancing (LVR) risk.

The trade-off is increased concentration and opacity: pricing logic becomes a black box, the AMM depends on a single operator, and transparency is weaker than in public, permissionless AMMs.

Taken together, the direction is clear: on-chain spot markets are steadily catching up in price competitiveness while preserving self-custody, censorship resistance, and reliable, always-on settlement.

Decentralized spot market risks

Execution frictions, how to avoid Maximum Extractable Value

MEV, or Maximal Extractable Value, is the extra profit that comes from choosing which transactions go first inside a block. When many users submit transactions that affect the same assets, the order in which they are processed matters.

Imagine three transactions waiting to be included in a block:

- Alice wants to buy ETH

- Bob wants to buy ETH

- A liquidity pool updates its price after each trade

If Alice’s trade executes first, she gets a cheaper price and Bob pays more. If Bob goes first, the opposite happens. The block proposer can decide this order—and can even insert their own trade in between—to capture the price difference as profit.

Because anyone can become a block proposer and blocks are built in a permissionless way, proposers are naturally incentivized to order transactions in whatever way maximizes their own returns. MEV is therefore not a bug, but a direct consequence of how decentralized blockchains process transactions.

In traditional finance, by contrast, exchanges are centralized and trusted to enforce neutral rules such as price–time priority. That neutrality is upheld through regulation, legal enforcement, and reputational risk. On blockchains, the anonymity and open participation of proposers mean these trust guarantees do not exist, turning transaction ordering itself into an arena for profit extraction. This makes the operation of active, competitive markets more challenging, as it incentivizes front-running of liquidity provision and other behaviors that leak value from liquidity providers to validators or other frontrunners.

One could still say that centralized exchanges exhibit their own form of MEV. It happens that high-frequency trading firms colocate their servers near exchanges to minimize latency and trade ahead of slower participants.

While MEV cannot be eliminated entirely, professional traders can significantly reduce their exposure through execution choices. Routing orders through private order flow or trusted builders instead of the public mempool prevents pre-trade frontrunning. Using RFQ or intent-based systems allows prices to be discovered off-chain and settled atomically on-chain, avoiding toxic dynamics. Finally, tight slippage limits, short deadlines, and order slicing help cap residual MEV.

Program Reliability

Decentralized exchanges operate as open programs that execute exactly as written. Like any software, they can contain errors, and in rare cases those flaws can be exploited, leading to losses.

Risk, however, is not uniform. Simpler protocols with a narrow scope that have been battle-tested over many years tend to be far safer than newer or more complex systems. Vitalik Buterin has recently argued that such “low-risk DeFi” programs, those that have stood the test of time, can reach a level of reliability comparable to traditional financial infrastructure, while still benefiting from the disintermediation enabled by blockchains. The overall trend is positive: relative to market size, the share of DeFi value lost to exploits has been declining in these mature markets.

Decentralized spot market for professional asset managers

Understanding liquidity provision

On a decentralized exchange, liquidity is provided through pools rather than through individual buy and sell orders. Liquidity providers deposit two assets into a shared pool (for example ETH and USDC), which the protocol uses to quote prices and execute trades automatically. When traders swap against the pool, the relative balances of the two assets change according to a predefined pricing rule, and liquidity providers earn a share of the trading fees generated by this activity. In effect, liquidity providers supply the capital that allows the market to function, and in return they are compensated for making continuous prices available to traders.

Earning yield through liquidity provision

For a professional asset manager, yield in decentralized spot markets is often generated through liquidity provision, where capital is deployed to support price discovery and execution in exchange for trading fees. Protocols such as Uniswap compensate liquidity providers for committing capital to the market, and with the introduction of concentrated liquidity, this activity has evolved into a form of active portfolio management. Capital is allocated into defined price ranges, or tranches, which determine when liquidity is active and earns fees. Narrow ranges increase capital efficiency and fee density, while wider ranges provide greater robustness across market movements, trading potential returns for reduced rebalancing requirements.

Effective liquidity provision therefore hinges on thoughtful tranche design. Rather than allocating capital into a single range, managers can segment liquidity across multiple tranches with different widths and placements, reflecting expectations around volatility, inventory tolerance, and operational intensity. Tighter tranches can be positioned near the prevailing market price to capture near-term trading flow, while broader tranches act as a stabilizing base that remains active through price fluctuations. As markets move, liquidity can be resized or rotated, transforming what was once a passive activity into a more systematic and repeatable process.

From a portfolio construction standpoint, the objective is not to maximize headline APY, but to optimize fee generation relative to capital usage and risk. Fee income must be assessed alongside inventory drift, rebalancing costs, and protocol-specific considerations. As tooling improves and on-chain markets deepen, liquidity provision increasingly resembles running a strategy rather than parking assets—rewarding managers who treat tranches as dynamic allocations within a broader on-chain portfolio.

Mastering liquidity provision risks

Impermanent loss

Impermanent loss describes the difference between the value of your assets inside a liquidity pool and what those same assets would be worth if you had simply held them outside the pool. When you provide liquidity, you are no longer holding fixed quantities of each asset. Instead, your position becomes a share of a pool whose composition continuously changes as traders swap against it. As prices move, the pool automatically adjusts its balances, and so does your exposure. The relevant comparison is therefore not “did I make money or lose money,” but “did providing liquidity perform better or worse than holding.”

As a result, the value of your LP position evolves differently from a buy-and-hold position. If one asset appreciates, the pool sells part of it to traders and increases its exposure to the other asset; if it depreciates, the pool does the opposite. This rebalancing smooths prices for traders, but it means that liquidity providers systematically give up some upside in trending markets and accumulate more of the underperforming asset. Impermanent loss is the gap created by this mechanism, and it becomes permanent once liquidity is withdrawn while prices remain away from their original ratio.

Protocol and smart contract risk.

Beyond market-driven effects, liquidity providers are exposed to protocol-level risk. Funds deposited into a DEX are controlled by smart contracts that implement pricing logic, fee accounting, and withdrawals. If these contracts contain a vulnerability, or if an upgrade or governance action introduces an error, capital can be lost or frozen regardless of market conditions. While this risk tends to decline over time for simple, well-audited protocols with long operational histories, it remains a non-diversifiable tail risk and a core consideration for any on-chain liquidity strategy.

Economic and market-structure risks (MEV).

Liquidity providers are also exposed to economic risks arising from how transactions are ordered and executed on-chain. Block latency and discretionary transaction ordering allow arbitrageurs and searchers to extract value through MEV, often by trading against stale prices or positioning themselves ahead of LP rebalancing. This value leakage reduces the net fees earned by liquidity providers and becomes more pronounced during periods of high volatility or congestion. While newer designs aim to mitigate or redirect MEV, it remains an inherent cost of providing liquidity in decentralized, block-based markets.

Letsgetonchain is an independent DeFi researcher. With a background as a TradFi market maker, he transitioned to DeFi as a core contributor to a credit protocol. Today, he writes about DeFi’s market structures, mechanism design, and protocol economics.